WrICE Workshops, University of the Philippines, Diliman

February 2017

Christos Tsiolkas and Norman Erikson Pasaribu

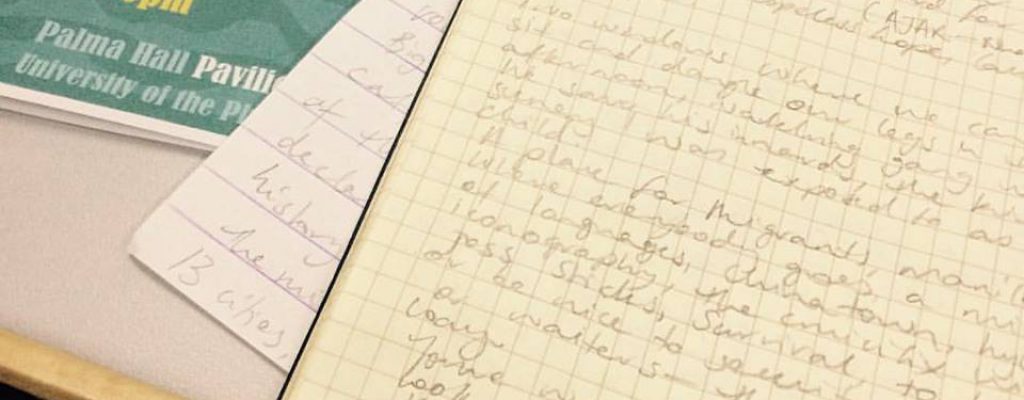

The setting for the first workshop is the University of the Philippines in Diliman. There’s a hushed scholarly atmosphere, the audience mostly made up of English department students and academics. The constant thrum of a large air conditioner is regularly broken by the click of an SLR camera.

Norman Erikson Pasaribu, award-winning Indonesian short story and poet, joins multi-award winning novelist, short story writer and playwright, Australian Christos Tsiolkas, at one end of a rectangular table formation to run a workshop exploring approaches to story-telling, with a focus on the use of imagery, language and characterization.

Tsiolkas reads an extract from his novel, The Slap (also adapted for television), in which one of his characters, Rosie, the mother of a young child, has a difficult phone conversation with her mother and recalls her experience of post natal depression.

Pasaribu reads a short story, ‘A lullaby for your long sleep,’ characteristically whimsical (but resonating with political undertones), his fusion of folklore and contemporary storytelling structured as a story within a story.

The two readings couldn’t be more different with Tsiolkas’s narrator firmly grounded in inner urban Melbourne, while Pasaribu’s narrative transcends or subverts the linear story so that it folds back on itself leaving the reader with a sense of dislocation in time and space, despite the tone being conversational and intimate. This promises to be a fascinating two hours.

Part 1 of this blog post will present thoughts on language and imagery, while Part 2 will address characterisation.

LANGUAGE, IMAGERY AND FOLKLORE

Both authors speak of how the length of their works, the structure and the language are determined by the story they want to convey.

Pasaribu remarks that by using simple earnest language, it allows the themes to come to the fore, that it prevents the reader from being distracted by the language. He notes the difficulty in translating his work, largely written in his native Bahasa, into English, that it flows better in Bahasa, however, that ‘the point of translation is to make something that wasn’t known, known.’ His work has been translated into English by Shaffira Gayatri and Syarafina Vidyadhana.

He shares the insight that through his time workshopping in Vigan with international writers, he has learnt that through different languages come different depictions of the world. The nature of the language itself contributes to the story told.

Tsiolkas notes that the structure of the novel has an effect on how he uses language, that with multiple changes in points of view, he is conscious he needs to keep the reader’s interest, so the language, by necessity, becomes very economical. Indeed the writing of both Pasaribu and Tsiolkas is characterized by the careful choice of words to construct simple but powerful sentences. The language is not ‘flowery’, rather it is considered.

Given that Tsiolkas, as an English speaker, is not tackling the same language issues, to him translation becomes a decision about form rather than dialect. He notes that his experience of working with poets and others writing in alternate forms in the past week has shown him a new way of telling stories that he’s keen to experiment with.

This leads to further questions and discussion relating to the form of the story, in particular, Pasaribu’s use of folklore and imagery in his work. He is asked whether the use of mythology is a deliberate device to disguise the political message. Will he still be read in Indonesia if he is more direct? His story from today makes reference to the mass killings in Indonesia in 1965-66, encapsulated in the following: ‘isn’t the denial of a genocide more heartbreaking than the act of killing itself?’

He points out that this is a stylistic choice more than a conscious decision about transparency, that the mixing of fable into the story strengthens it. He remarks that historians are already making direct reference to these events in their textbooks. This seems an apt illustration of the potency of the arts in promoting understanding through indirect means. Perhaps the points raised are also a timely reminder of how, in Australia, we have taken for granted the freedom to openly express opinion without fear of retribution. Does this mean that, in Australia, we have had less need to employ folklore and fables in our story-telling, or alternatively, that Anglo-Celtic Australians have become disassociated from their original oral tradition?

I recall a conversation with Pasaribu in which he talked about the Indonesian newspapers reporting folklore as fact, and how quaint that seemed. This discussion goes to the very core of the concept of ‘truth’, how it is affected by context, that culture is context. For many thousands of years humans have used fables or myths both to entertain and to convey the political or social rhetoric of the time, whether to encourage compliance, faithfulness or generosity. Perhaps as an agnostic Anglo-Celtic Australian I have become disconnected from my oral tradition, the folklore and mythology that guided my ancestors.

Another audience member suggests that the story within a story structure is not tolerated well by English speakers and that there is a suspicion of folklore tradition, also proposing that this mode of storytelling is not popular with English readers any more. Pasaribu points to the strong tradition of invoking folklore in Indonesian story telling. Indeed one only needs to scan the shelves of local bookstores to see that this style of story-telling does in fact seem to have a wide following as pointed out by Filipino author Darryl Degano. Its ‘sister’ in predominantly English speaking countries, ‘magical realism,’ is certainly a popular genre in Australia. Indeed, Australian WrICE participant, awarded indigenous poet and short story writer, Ellen Van Neervan, employs elements of magical realism in her anthology Heat and Light to explore political themes.

This poses an interesting reiteration of the point that perhaps we too often look to the west, to the USA and UK for our story-telling techniques, Tsiolkas noting that the incorporation of folklore into story is ‘wonderfully seductive’ and could be effectively used to tell a story in English.

The use of folklore in story-telling among the Asian and Pacific writers on this residency has provided insight and inspiration for the non-indigenous Australian writers, who have been more often influenced by Western practices. It’s a great reminder of the value of this time of cultural exchange provided by the WrICE experience, and how our writing can be enriched and challenged by these connections. Today’s discussion was a taste of this.

Jennifer Porter